Emrah Coban, science co-ordinator for wildlife charity Kuzeydoga, uses a radio aerial it retrieve data from tagged wolves in the Sarikamis forest.

If you get depressed following ecological issues in Turkey, a trip to Kars might cheer you up. Inspiring things are happening in this remote, snowy corner of the country.

I recently went there to write about nature NGO Kuzeydoga and the creation of Turkey’s first ‘wildlife corridor’: an ambitious plan to link the isolated Sarikamis Forest with larger wildernesses bordering the Caucasus.

As I’ve written before, Turkey’s ecological situation is at once awful and fascinating: extraordinary biological wealth threatened by grandiose development plans, with virtually no-one knowing or caring.

But in Kars, a tiny community of ecologists have carved out a series of surprising local victories. I’ve become fascinated by their work, and by the reasons behind their success.

Turkish civil society movements of all kinds operate within a constrained space. Whatever field they are working in, Kuzeydoga’s example might offer valuable insights.

Februarys in Kars are very cold, partly why I wanted to go there this time of the year. Kuzeydoga’s founder Cagan Sekercioglu often criticizes Turkish conservationists for spending too much time in big cities, and for being unwilling to live in the sticks, where their presence is needed. But one of the distinctive things about Kuzeydoga, to hear him tell it, is that its entire operation is based in Kars year-round.

The plan was to go wolf tracking, and I had visions of dogged conservationists ploughing through drifts of snow on remote forest tracks. It wasn’t quite like that, though not entirely different either.

The snow and the cold were certainly there. One morning the temperature sunk to -26C, and the diesel froze in the fuel lines of the Toyota Land Cruiser. It took an hour to flush out. We had hoped to check camera traps around the forest, but there was too much snow, and as it turned out, wolf-tracking is a less romantic business than its name suggests.

Kuzeydoga have fitted GPS collars with mobile phone chips to two wolves, ‘Kuzey’ and ‘Doga’, an old one-eyed male and another younger male. Once a week, the ecologists go to the top of a hill overlooking the forest, wave an aerial across the horizon until they pick up the signals, then download the data, telling them where the wolves have been for the past week.

There is a ski resort near Kars with lifts up to the summit of a big hill that serves this purpose well. When we downloaded the data, the wolves themselves were several miles away and well out of sight.

This is the first time anyone has tracked wolves in Turkey, and the information gleaned from Kuzey and Doga over the past four months has been key to convincing the government to create the wildlife corridor.

Since October the younger wolf ‘Doga’ has ranged across an area 13 times larger than the national park itself, demonstrating that there is not nearly enough protected habitat to support the wolf population.

By monitoring the camera traps, collecting and identifying animal faeces from the forest, and dissecting dead wolves, they have gained even more alarming insights.

Part of the problem with conservation in Turkey is that so little research has been done that its difficult to assess how much danger threatened species are facing.

According to one estimate, there are a total of 7,000 wolves left in Turkey, but this is a blind guess, according to Kuzeydoga’s chief science officer Emrah Coban.

In Sarikamis, considered a stronghold for wolves, there may only be around 25 remaining. In the past year alone seven have died as a result of human contact (shot, killed by dogs, hit by cars).

There are a greater number of bears (around 50, they believe) and because these hibernate during winter and generally stick to the woods fewer are killed by people. As few as eight Eurasian Lynxes may remain.

Just as worrying is the extent to which the wolves appear to rely on domestic livestock for their survival. In a healthy forest, prey species will outnumber predators by a ratio of 10:1 to 100:1. In Sarikamis the figure is as closer to 1:1, with roe deer hunted virtually to extinction and wild boar scarce.

In a healthy environment, wolves fatten in the winter, when the snow gives them an advantage against their prey. But in Sarikamis they get thinner, and Sekercioglu speculates that this is because during the winter, livestock are kept safely in sheds, depriving them of what is perhaps their primary food source.

Villagers living close to the Sarikamis Forest discuss a presentation about Kuzeydoga’s work.

So predator-human conflict around Sarikamis is intense. This became very clear when I visited villages with Kuzeydoga as they gave powerpoint presentations aimed at convincing locals not to shoot wolves, and explaining the corridor project and the benefits of the forest.

Particularly in villages whose inhabitants kept sheep rather than cows, the hostility to wolves went bone deep. Photos showing Kuzeydoga volunteers releasing orphaned wolves into the wild evinced gasps of disapproval.

Some of the reactions to the corridor were even more extreme. “This is an Armenian plot,” muttered one farmer when shown a map of the projected route. Another stormed out of the room declaring that it was the first step in a government scheme to rob them of their grazing land.

But in all five villages we visited, I left with the feeling that something had been achieved, no matter how small it might be.

Mainly, there was a sense that people were impressed by what the ecologists were doing, even if some remained baffled by their motivations.

It was the third time Kuzeydoga had visited the villages. The first two times had been spent surveying residents about their views on the forest, its wildlife, and how to deal with wolves. This time they presented the survey results, as well as mapped data from the tracked wolves. They also gave practical information on a little-known government compensation scheme for those who had lost livestock to predators.

They encouraged people to protect their animals with electric fences, which some of the farmers apparently never knew existed. By far the popular element in the presentation were the videos showing the fences’ deterrent effects on various animals, which were met with gales of laughter. Some discussed the possibility of getting funding from an agricultural bank in order to do an electric fence pilot scheme.

Business cards were handed out, and the day after visiting one village, its mukhtar called to say they had found a wounded bird and thought it was a bittern: would they come to pick it up? They did, and took it to Kafkas University’s veterinary faculty (it was in fact a red-necked grebe).

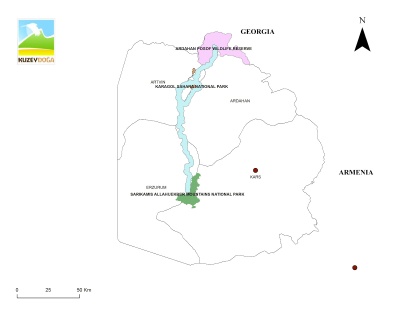

A map showing the projected corridor route (in blue), linking the Sarikamis-Allahuekbar National Park with the Ardahan Posof Wildlife Reserve, which adjoins forests in Georgia. Courtesy of Kuzeydoga.

I tend to get skeptical when NGOs talk about ‘building awareness’, which seems to me a pretty nebulous concept. But the Kuzeydoga team have a strategy that seems to be working well.

Whether dealing with government ministers or impoverished shepherds, they take care not to come across as misty-eyed environmentalists. They present solid research, gathered over years. They zero in on areas of common interest, offer straightforward suggestions, and give practical advice on how to implement them.

They are also not encumbered by the intense ideological enmity that large sections of Turkey’s NGO community, environmental and otherwise, bear towards the government.

From speaking to Kuzeydoga’s staff, it was apparent that they were not all fans of the AKP, but were still able to drop any ideological baggage they may carry for the sake of their work.

As Sekercioglu points out in the previous post (paraphrasing a documentary): “There is no socialist air, there is no Islamist air, there is no nationalist air, there is only air. And if you breathe air, that makes you part of the environment and if you are concerned about clean air, I would consider you an environmentalist!”

The results of this approach are most apparent in Kuzeydoga’s work on the corridor. The Turkish government’s environmental credentials may be miserable, but one thing it is good at is reforestation. Soil erosion is a problem that has scared successive governments, and in 2009 alone 45,000 hectares of woodland were planted. Turkey’s forest cover is actually increasing.

“We said to the ministry: You are planting these trees anyway, so if you plant them where they provide ecological connections, you will help the wildlife as well,’” explains Sekercioglu.

It was in 2008 that Kuzeydoga first went to what was then the Ministry of Environment and Forests to present them with the corridor scheme. For three years nothing happened, until the project fell under the eye of a high-ranking minister. He he liked it, and it got the green light.

It was the same at nearby Lake Kuyucuk. Having secured its protection, Kuzeydoga addressed the issue of a disused road that bisected the lake, causing drainage and environmental problems.

They came up with an elegant solution: cut either end off the road and add the displaced soil onto the centre section, turning the remains of the road into a nesting island for birds.

When they presented the idea to the governor of Kars on a Friday in March 2009, he was so taken with it that he sent the bulldozers in on the Monday.

“Just like that, the governor gave us two excavators, one bulldozer and two trucks, for two months. They worked around the clock and the government paid for all of it,” recalls Sekercioglu. Now, at least 200 birds nest or roost on the island, safe from humans, livestock, and predators.

“This was so exciting because it was a major environmental construction project. In the US, just getting the authorization for this would take years.”

A Common Kingfisher at wetlands in Igdir, near the Armenian border.

It’s a sad fact of biodiversity conservation everywhere that while victories are never final, losses often are.

While it’s impressive what Kuzeydoga have achieved with only three paid employees covering an area the size of Armenia, it’s also clear that they have picked their battles carefully, and the fragility of their gains is painfully apparent.

“It’s partly to do with Turkey’s centralization of power,” explains Sekercioglu. “If you convince the right person, you can do a lot of good very fast. Of course it also works the other way: a lot of bad is done very fast.”

Will the wildlife corridor really materialize? Will it come in time to save the wolves, lynxes and other wildlife that would benefit from it? It will surely be 15 years at least before the saplings provide adequate cover, and who’s to say that in the meantime the government will not decide to build a dam or a road to cut through it?

Nonetheless, there’s an exciting synergy to Kuzeydoga’s work. The charity’s headquarters in Kars have become a stopping place for a variety of people interested or inspired by their work.

Other Turkish ecologists are said to be preparing plans for wildlife corridors and bird-nesting islands. And in Kars, American Cat Jaffee is launching Balyolu, an ecotourism venture based around the region’s traditional beekeeping industry and designed to benefit local women.

“It is like turning around a very big ship,” says Sekercioglu. “It will happen slowly but we have to keep pushing.”

Two rescued wolf cubs at Kafkas University’s veterinary faculty, Kars. Three cubs were taken by local farmers who discovered their den and hoped to raise them as guard dogs. All three were released into the wild at five months old. One was killed by a car in the past week, another was likely shot. Photograph copyright Carolyn Drake.